Far, Far from Ypres ‘Lest We Forget’

Far, Far from Ypres ‘Lest We Forget’

“How many of you have ever experienced war first hand?” That question was posed to a group of people ranging in age from their early twenties to their late sixties. The answer was none, but several of them had sung songs about it.

The context in which the question was posed was a group of people exploring issues in a summer school dialogue session on leadership. The workshop leader that day was a retired Lt Colonel of the British Army. He had spent his working life, in his view, as a peacekeeper, and had served in many of the conflicts that most of us have seen through our television screens. He confessed later that he sometimes gets angry when hearing people singing about war. The discussion later was of how privileged a generation we are, but there was a degree of gloom about the future. Global warming and the very real threat of conflict over resources led to hard questions about the legacy that we will leave to the next generation.

Given that few of us have experienced war first hand, it is interesting to consider where our views come from. Many of us were brought up with war as the backdrop for adventure stories. War was glorious, we always held the moral high ground, the enemy were baddies and it was all very clean. The reality is different but films that attempted to show the nasty side of war were not necessarily good box office and increasingly the move is towards the fantasy conflict; Star Wars et al.

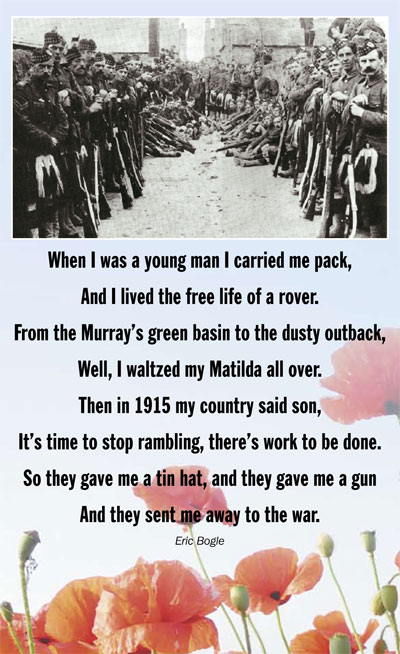

Many songs about war are also ‘a good sing’, but a few songs have really gripped us. The words of Eric Bogle’s anti war songs will be familiar to almost every person who listens to folk music. ‘And the band played Waltzing Matilda’, was written from an Australian perspective, but its message is universal. Few songs have generated such reaction. News of ‘that song’ was in the folk press well in advance of most people hearing it. The news story at the time was not about the song, it was about people’s reaction to the song.

There has been a similar reaction from anybody who has visited the war graves in France and Belgium and it was a visit to these war graves that led Ian Green to ‘Far, Far From Ypres’, a tribute in song, music and poetry to the soldiers who fought (and died) in World War 1. The initial project was to record the soldiers’ songs but soon developed into a more comprehensive tribute. Far, Far From Ypres uses a double CD format, one CD concentrating on the soldiers’ songs, the other provides a deeper exploration of wider issues though song, poetry and music both from the period and more modern material. This second CD contains some of the most powerful anti war writing there is. Each song or poem has its own impact, but the result of bringing them together as a collection adds to their power.

A quarter of all the young men to die in the British Army in the Great War, died to prevent the little Belgian town of Ypres from falling into German hands. It is simply known as, “The Graveyard of the British Army”. Over half a million men, from both sides, died in the Ypres Salient during the war. The names of 55,000 men of the British and Empire Forces who have no known grave, are inscribed on the vast Menin Gate at Ypres. A further 35,000 names of the missing who could not be fitted into the vast Menin Gate, are inscribed on the back wall of the great British Military Cemetery at Tyne Cot, below Passchendaele Ridge.

‘Far, Far from Ypres’ has a more distinctly Scottish perspective than any of its predecessors, but like Eric’s song, the sentiments transcend borders. Scotland suffered the most soldiers killed, per head of population, of any nation who had fought in the conflict. That is reflected in the startling statistic that despite making up only one tenth of the British population, Scotland suffered one fifth of the British losses.

The subject matter contained in this double CD has never before been covered in such depth. The most frequent comment has been that it was about time that someone did this. In addition to the many soldier’s trench and marching songs, plus music hall songs, some of the best songs, music and poems written about ‘the war to end all wars’ by the finest of writers are included. Ian Green is reported to be “desperately proud of what has been achieved on this double CD.”

The project was first suggested to Ian Green by an ex-police colleague, Jim Paris, who shared with Ian an insatiable interest in the history of World War 1. Jim’s father served with the Scots Guards during the latter part of the Second World. After he was demobbed, settled back into civilian life, married and became a tradesman. A chance meeting with an old Guards mate led to him joining The Scots Guards Association Club in Edinburgh. As a result when Jim was a boy he attended many Scots Guards picnics and Christmas parties and has many happy memories of those days. One picture, though, is vividly etched on his memory, and that was the old men who frequented the club, who had fought in The Great War of 1914 -1918. Mostly they were quiet and reflective men with a wicked sense of humour. Speaking to them and listening to their stories drove him to find out more about the First World War and the men who fought in it.

Jim soon learned that the Great War shaped the rest of the 20th Century and that we still live with its legacy in the 21st. He found out that his father had been named after his Uncle, James Paterson who had been killed at the Battle of Loos in 1915 while serving with The Gordon Highlanders. He was just 18. “I support Heart of Midlothian Football Club, and as a young lad would attend the annual Armistice Service at The Hearts War Memorial at Haymarket junction to remember the Hearts players who had volunteered in 1914 for the 16th Royal Scots (McCrae’s Battalion) and died in The Great War. I learned that these same old men who I spent time with were some of the very few survivors from The Scots Guards, who were almost completely wiped out in the battles of 1914.”

In 1999 Jim went on a Great War Battlefield Tour with Mercat Tours International, led by Des Brogan and was deeply moved by what he saw and experienced. “Des has been taking young people on these trips for 25 years and they have been changed by their experiences. On the trips young people learn the songs the soldiers sang all these years ago and by the end of their experience know them off by heart and are always requesting a singalong.”

Jim subsequently became a Battlefield Guide for Mercat Tours and in 2004 with Des Brogan, their managing director, jointly presented their ideas to Ian for a project to have these soldiers’ songs recorded professionally. Lack of resources meant the project was placed on the ‘back-burner’ but a turning point came in 2007 when Des Brogan invited Ian and his wife June on one of the WW1 coach tours of Flanders. The trip had a direct personal connection as June was able to fulfil a dream and visit her Grandfather McLennan’s grave in one of the many War Cemeteries. Although Ian had read numerous books on WW1, the tour of cemeteries and battlefields in Flanders had a profound effect on him. He was very emotionally affected by the trip and now believes that everyone should consider the trip to Flanders.

Ian returned home convinced the project should receive priority status and started planning it immediately. The choice of producer, someone who could pull together the right voices and instruments for the new recordings of songs for the first CD, was obvious to Ian - Ian McCalman of The McCalmans folk group.

“I think this project took a strange route to get to the end of its journey. It started out as an email from Ian Green saying that he was thinking about an album based on the trench songs of the First World War and would I be interested. It sounded like something that I could arrange so, of course, I said yes. A few weeks later I met up with him to discuss the songs etc., and then I realised the scale of the project. I ended up recording 35 songs, some short and others full length, but all of them were recorded with an intensity that I hadn't experienced before. I wanted to make them accurate representations of the originals so I had to ask singers, who were known for either their own songs or original interpretations of existing songs, to forget that concept and put themselves into the heads of soldiers singing with their mates. Sorry guys, forget the voice techniques, the idiosyncratic syncopation, the little phrasing tricks ... sing it straight and from the heart.”

“Some of the songs completely ‘got to me’ and I gradually became immersed, to the point of obsession, in the whole project. Some of the trench and marching songs had such a message of sadness and hopelessness that, perhaps, it needed someone with a little less imagination to deal with them day after day. Their anger was almost exclusively directed at their superiors rather than ‘the enemy’. Their hopeless boredom was awful. Terrified boredom!”

“The music hall songs were obscene in their lack of subtlety. For instance, sexual favours were openly offered for anyone joining up and a message, in a seemingly innocent song, said that, ‘we won't like it when you don't come back, but us ladies would rather you went (to war)’. The contemporary songs were an eye-opener as well with songs like ‘Black is the Sun’ causing a necessary break in recording whilst the engineer (me) got himself together. It really doesn't need any of us to say ‘war is bad’, ‘war is unnecessary’, ‘war is a waste’, ‘war is criminal’ etc., because the people that really know wrote and sang the songs on the first album and the people that are eloquent enough to observe and ‘comment’ on the cruel subtleties of the 14/18 war did so on the second album.”

World War 1 was the first ‘total’ war which affected the entire population. Consequently it became as important to maintain the morale of the workers on the Home Front as it did for the soldiers on the Western Front. Indeed, quite often, the music of the Home Front was aimed directly at the soldiers, such as the romantic ‘Roses of Picardy’ or the patriotic sentimentality of Ivor Novello’s ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’.

The soldiers had many reasons to sing. Often it was to fend off boredom. It is not well known that soldiers spent only on average three or four days per year in battle. The rest of the time was spent on fatigues, training exercises, forced marches and maintaining life in increasingly uncomfortable surroundings in the trenches. Sometimes they sang to keep their spirits up and to prevent them from showing their fear to their pals, hence the relentless cheerfulness of ‘Pack Up Your Troubles’. Often they sang because in the lunacy of trench life when the only way to cope was to employ sardonic black humour. The content of ‘Hush! Here Comes A Whizz Bang’, ‘Bombed Last Night’, ‘Gassed Last Night’, and ‘Fritzy Boy’ make sense when you realise that the best way to live constantly with the threat of sudden and violent death is to laugh at it.

The soldier’s songs are a rich source of information for the historian since they provide a window into the life and thoughts of the first ever Citizen Army fielded by Britain. Early songs betray an innocence about the reality of trench life … and death. Although a note of resignation creeps in with ‘We’re Here Because We’re Here’ later songs still display that stiff upper lip and black humour of ‘Living In A Trench’ and ‘Minor Worries’. It is only as the war drags into a third and fourth year that the songs begin to betray a bitterness which was hitherto lacking. ‘Joe Soap’s Army’ is aimed at the perceived mistaken strategies of a General Staff that does not share the dangers of trench life with the ordinary Tommy.

The final songs have changed in tone and sentiment from the early chants. They are still as tuneful, but with a quite different tone as the carnage of the war has become obvious and the Citizen Army has lost its innocence. The songs ‘I Wore a Tunic’, ‘I Don’t Want To Be a Soldier’, ‘I Want To Go Home’ and ‘If You Want The Old Battalion’ make the soldiers’ intentions quite clear.

The singers gathered to record the soldiers’ songs were Ian Bruce, Fiona Forbes, Stephen Quigg, Ian McCalman, Tich Frier, Nick Keir and Hamish Bayne, collectively appearing under the title of ‘The Scottish Pals Singers’ and permission was given to include an archive recording of Sir Harry Lauder. Musicians included Maartin Allcock, Hamish Bayne, Nick Keir and Ian McCalman. The pipers and drummers were from The Army School of Bagpipe Music and Highland Drumming, Redford Barracks, Edinburgh and included Pipe Major Neil Hall, Pipe Sergeant Paul Tweedley, Corporal Peter MacGregor, Corporal David Dodds, Corporal Neil McNaughton, Piper James Craig, Drum Major Brian Alexander, Corporal Simon Grant, Corporal Allan Campbell, Corporal Simon Phillipps and Lance Corporal Martin Brown. Bugler John Samson played The Last Post.

Contributors to the second CD included The Corries, Jim Malcolm, Steve Palmer, The McCalmans, Robin Laing, Eric Bogle, Roddy MacLeod, Sheena Wellington & Karine Polwart, Dick Gaughan, Malinky, Alan Bell, Heather Heywood and Dougie Pincock. The narration was by Iain Anderson and the poetry includes two gems from the pen of Scotland’s soldier poet, Ewart Alan Mackintosh.

The track record of this project is that is has a deep impact on those who get involved. Where it may go next is not immediately obvious but live performance seem to be a natural development. It wouldn’t necessarily be an easy step given the scale of the contributions, but some things have an imperative that can drive people to overcome obstacles - Lest we forget.

On the slopes of the village of Ovillers lies a cemetery with an awful secret. It contains the bodies of 3,265 British soldiers, which is not exceptional in itself given the number of similar sized cemeteries in the area. Ovillers’ secret lies in the fact that 72% of the soldiers there are ‘Known unto God’, one of the highest percentages of unknown concentrations on the Somme.

One of the few soldiers who have an identified grave is Captain John Lauder of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He was killed on 28 December 1916 and was the only son of the famed Scottish music hall star, Sir Harry Lauder. It is said that Harry was told of the death of his only son as he was going on stage. Despite heartbreak and grief, Sir Harry performed as well as ever that evening but when he came off stage he wrote, what was to become one of his most famous songs, ‘Keep right on to the end of the road’.

Keep right on to the end of the road,

Keep right on to the end,

Tho' the way be long, let your heart be strong,

Keep right on round the bend.

Tho' you're tired and weary still journey on,

Till you come to your happy abode,

Where all the love you've been dreaming of

Will be there at the end of the road.

I walked from Ypres to Passchendale

In the first grey days of spring

Through flatland fields where life goes on

And carefree children sing

Round rows of ancient tombstones

Where a generation lies

And at last I understood

Why old men cry

Dick Gaughan

Did they beat the drum slowly, did they play the fife lowly

Did they sound the death march as they lowered you down

Did the band play the Last Post and chorus

Did the pipes play the Flowers of the Forest?

Eric Bogle

“This album is a tribute to all the soldiers of these islands, from Scotland, England, Ireland and Wales and also their Commonwealth brothers in arms from all corners of the globe who suffered and died with them, in The Great War for civilisation. We can only hope that it inspires everyone who listens to it to visit the bloody fields of Flanders and France and see where the flower of our nation lies. This is their legacy and we owe our freedoms to them.”

Jim Paris

Far, Far, from Ypres - Songs, Poems and Music of WW1 Greentrax Recordings CDTRAX1418